It doesn’t take a psychic to predict that this year’s election season will feature plenty of debates on Social Security and education. Usually, the two hot-button topics are addressed separately, as few people see a direct link between paying for schools and funding retirements.

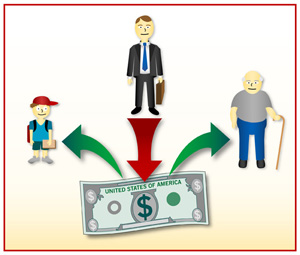

But the two issues should be linked, says economist Michele Boldrin, the Joseph Gibson Hoyt Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. In the same way that younger generations take care of their elders as a kind of “return” on their parent’s investment, so too can the U.S. invest in the educational needs of its children and have the accumulated debt be paid off to retirees when it comes due.

The key is to virtually do away with paying for schools through property taxes and to stop funding public pensions through the social security tax.

“The cost of education should be treated as an accumulation of debt toward the older generations,” Boldrin says. “From the time students start kindergarten until the time they finish their education, they are, in a certain sense, taking on debt toward the older generation; a debt that should be repaid when they enter the workforce. The debt could be paid off like a mortgage in fixed amounts every month or all at once. Either way, that money would be an individual’s social security contributions. The proceedings so obtained would go toward paying part of the pensions.”

Under the current system, people who don’t have children, or whose children are grown don’t have an incentive to pay for schools. This is shortsighted, says Boldrin.

Based on research he conducted with Ana Montes at the Universidad de Murcia in Spain and other coauthors, Boldrin says publicly financing education should be viewed as a loan from the middle-aged to the young generation.

“The loan finances a young person’s accumulation of human capital. Twenty years from now, those children are going to be working and will contribute to the economy. As they repay the capitalized value of their education, they pay back their debt to the previous generation,” he says.

When it comes to funding the retirement pensions, Boldrin says that the amount that each individual contributes toward financing the educational debt is capitalized at the market rate of interest. That accumulated capital would then be paid out, in the form of annuities, to the same citizen once retirement age is reached.

“Our research model suggests that public education financing and properly redesigning the public pension system could go a long way toward enhancing economic efficiency and long-run welfare,” Boldrin says.

Boldrin’s research is published in The Review of Economic Studies, 2005.

Editor’s note: Professor Boldrin is available for live or taped interviews using Washington University’s free VYVX or ISDN lines. Please contact Shula Neuman at (314) 935-5202 for assistance.