Bret Gustafson, Ph.D., assistant professor of anthropology in Arts & Sciences, has spent more than 14 years in Bolivia.

His early research focused on language and culture to help promote the inclusion of the indigenous Guarani language, history and culture into the public school system in Bolivia. As with many indigenous peoples across the Americas, the education system has long been biased against native peoples. It has sought to do away with their languages and their specific identities.

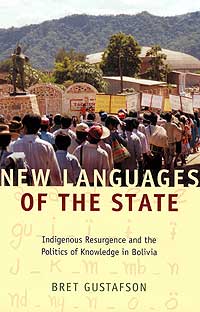

Recently, Gustafson’s research has expanded beyond the Guarani into an ethnographic study of the Bolivian state. This research sought to use ethnography to shed light on a complex process of education reform.

“Anthropologists traditionally work in small communities and are expected to discover something unique about a particular place or culture,” he said. “Yet, today’s anthropologists of my generation are also looking at complex social and political processes, at different scales.

“So, my purpose was to understand how large-scale development projects like school reform — much of it financed by external donors — intersected ongoing political and social conflicts at different levels of Bolivian society,” he said.

Through researching his new book, Gustafson found that education reform at the level of the centralized government was more about the restructuring of state bureaucracies — and the political relations that sustained these — than it was about the actual education outcomes, or the issue of indigenous rights. This contradicted how donors talked about their aid and its purposes.

“At the level of local movements like the Guarani, education also had a political meaning,” Gustafson said. “It was about language and cultural rights, and the Guarani did work to improve their schools. This in itself was significant. However, it also was used to gain a larger voice in the regional and national society. It thus had a kind of democratizing effect, even though this was not how many elites imagined its purposes to be.”

The book retraces the conflicts and debates over schooling and looks in-depth at how different personal histories come together in this complex development project. It concludes that, however limited, the transformation of national education systems to recognize indigenous rights does have democratizing effects rather than creating radical extremists, which many opponents of indigenous schooling argue.

The book has relevance to scholars of many disciplines who study international development.

“Though deeply rooted in Bolivian history, culture and politics, this work sheds light on a global dilemma: how to create models of state and society that include people in the opportunities of knowledge and economy without marginalizing them racially or culturally or denying them their particularity,” Gustafson said.