American Journal of Pathology (used with permission)

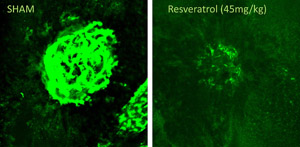

On the left, abnormal blood vessels are seen in bright green underneath the mouse retina, but in the image on the right after resveratrol treatment, few abnormal vessels are present.

Resveratrol — found in red wine, grapes, blueberries, peanuts and other plants — stops out-of-control blood vessel growth in the eye, according to vision researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The discovery has implications for preserving vision in blinding eye diseases such as diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration, the leading cause of blindness in Americans over 50.

The formation of new blood vessels, called angiogenesis, also plays a key role in certain cancers and in atherosclerosis. Conducting experiments in mouse retinas, the researchers found that resveratrol can inhibit angiogenesis. Another surprise was the pathway through which resveratrol blocked angiogenesis. The findings are reported in the July issue of the American Journal of Pathology.

“A great deal of research has identified resveratrol as an anti-aging compound, and given our interest in age-related eye disease, we wanted to find out whether there was a link,” says Washington University retina specialist Rajendra S. Apte, MD, PhD, the study’s senior investigator. “There were reports on resveratrol’s effects on blood vessels in other parts of the body, but there was no evidence that it had any effects within the eye.”

Apte

The investigators studied mice that develop abnormal blood vessels in the retina after laser treatment. Apte’s team found that when the mice were given resveratrol, the abnormal blood vessels began to disappear.

Examining the blood-vessel cells in the laboratory, they identified a pathway — known as a eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase (eEF2) regulated pathway — that was responsible for the compound’s protective effects. That was a surprise because past research involving resveratrol’s anti-aging effects had implicated a different mechanism that these experiments showed not to be involved.

“We have identified a novel pathway that could become a new target for therapies,” Apte says. “And we believe the pathway may be involved both in age-related eye disease and in other diseases where angiogenesis plays a destructive role.”

Previous research into resveratrol’s influence on aging and obesity had identified interactions between the red-wine compound and a group of proteins called sirtuins. Those proteins were not related to resveratrol’s effects on abnormal blood vessel formation. Instead, the researchers say that in addition to investigating resveratrol as a potential therapy, they also want to look more closely at the eEF2 pathway to determine whether it might provide a new set of targets for therapies, both for eye disease and other problems related to abnormal angiogenesis.

Apte, an assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences and of developmental biology, says because resveratrol is given orally, patients may prefer it to many current treatments for retinal disease, which involve eye injections. The compound also is easily absorbed in the body.

In mice, resveratrol was effective both at preventing new blood vessels and at eliminating abnormal blood vessels that already had begun to develop.

“This could potentially be a preventive therapy in high-risk patients,” he says. “And because it worked on existing, abnormal blood vessels in the animals, it may be a therapy that can be started after angiogenesis already is causing damage.”

Apte stresses that the mouse model of macular degeneration they used is not identical to the disease in human eyes. In addition, the mice received large resveratrol doses, much more than would be found in several bottles of red wine. If resveratrol therapy is tried in people with eye disease, it would need to be given in pill form because of the high doses required, Apte says.

There are three major eye diseases that resveratrol treatment may help: age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity. Age-related macular degeneration involves the development of abnormal blood vessels beneath the center of the retina. It accounts for more than 40 percent of blindness among the elderly in nursing homes, and as baby boomers get older, the problem is expected to grow, with at least 8 million cases predicted by the year 2020.

In diabetic retinopathy, those blood vessels don’t develop beneath the retina. They grow into the retina itself. Diabetic retinopathy causes vision loss in about 20 percent of patients with diabetes. Almost 24 million people have diabetes in the United States alone.

Retinopathy of prematurity occurs when premature babies with immature retinas experience an obstruction in blood flow into the retina. In response, those children often develop abnormal blood vessels that can cause retinal detachment and interfere with vision. Worldwide, that condition blinds 50,000 newborn babies each year.

Apte says the pathway his laboratory has identified may be active not only in those blinding eye diseases, but in cancers and atherosclerosis as well. If so, then one day it might be possible to use resveratrol to improve eyesight and to prevent cardiovascular disease and some types of cancer, too.

Khan AA, Dace DS, Ryazanov AG, Kelly J, Apte RS. Resveratrol regulates pathologic angiogenesis by a eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase-regulated pathway, American Journal of Pathology, vol. 177, pp. 481-492. July, 2010. DOI:10.2353/ajpath.2010.090836

This research was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, the Carl Marshall Reeves and Mildred Almen Reeves Foundation, Research to Prevent Blindness, the International Retina Research Foundation, American Federation for Aging Research, American Retina Foundation and an IRRF Callahan Award.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.