Forty years ago, fate sprung an ambush on Michael J. Welch. Welch, born and raised in the English city of Stoke-on-Trent, had just earned a Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of London and was on his way to Brookhaven National Laboratory in the United States for a postdoctoral appointment. He had filled out all the paperwork necessary for a two-year student exchange visa and brought it to the American embassy in London for processing.

The clerk who interviewed Welch asked why he was putting in for an exchange visa, as though the idea just didn’t make any sense.

“I said, ‘I don’t know, it’s what they sent me,'” Welch remembers, lowering his already deep voice and shrugging his shoulders in playful mockery of his own youthful diffidence.

“And the clerk said, ‘You should be an immigrant!'”

Welch took the clerk’s advice and filled out a new set of forms and paperwork for an immigration visa.

Now 66 and a professor of radiology, of chemistry in Arts & Sciences and of molecular biology and pharmacology, Welch is still clearly amused that such a fateful turn in his life was prompted by a chance encounter with a complete stranger.

However, his next step toward the place where he has spent his professional life was much more deliberate.

As his postdoctoral fellowship at Brookhaven drew to a close in 1967, Welch had two job offers from university chemistry departments but declined them to come to Washington University and label compounds for Michel Ter-Pogossian, Ph.D., a physicist who was a pioneering developer of the scanning technique known as positron emission tomography, or PET.

“My colleagues at Brookhaven all thought I was crazy — they thought I was coming to Washington University to become a medical technician,” Welch says.

“But I had done my Ph.D. on work with radioactive compounds, and the idea of applying that type of technology to medical problems seemed very exciting to me. Which it has been for 38 years.”

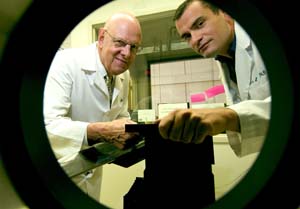

Welch, who specializes in the synthesis of new radioactive chemicals for medical imaging, is head of the Radiochemistry Laboratory Institute at the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology and a member of the Senior Leadership Committee of the Siteman Cancer Center.

Welch is also principal investigator for the University’s longest continuous NIH grant, “Cyclotron Isotopes in Biology and Medicine,” which two years ago was renewed through 2008, the grant’s 44th year of operation.

Welch inherited leadership of the grant from Ter-Pogossian in 1984. It previously focused on studies of imaging agents useful for neuroscience but now is directed toward the development of imaging agents that can help researchers better understand the connections between diabetes and heart disease.

“Cardiovascular disease is the most frequent cause of death in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and diabetics have a much higher incidence of hardening and narrowing of the arteries and of dysfunction in the pumping chambers of the heart,” Welch explains.

Evidence has shown that diabetics have abnormal accumulations of fatty substances known as lipids in the myocardium, or middle wall of the heart. Scientists think this buildup promotes the creation of chemically reactive nitrogen and oxygen compounds that damage heart tissue.

Through this and other grants, Welch leads what colleague Barry Siegel, M.D., professor of medicine and radiology, calls a “small army” of researchers dedicated to developing new imaging agents.

“He has a very complex operation going on, with many different lines of research,” Siegel says of Welch, whom he has known for 35 years. “He is a spectacular chemist who can quickly size up a project that a graduate student or postdoc has been working on and provide needed insight to sort of cut through the Gordian Knot and get things moving again.”

Siegel, who has led the Division of Nuclear Medicine at Barnes-Jewish Hospital since 1973, recalls giving a symposium presentation where he described his division’s research mission as “primarily … to serve as Michael Welch’s translational laboratory.”

Siegel was only half joking — the division he heads is a large one with a diverse array of research. But applying in humans the agents Welch’s group develops in the laboratory and in animal models has kept them very busy.

“Mike is very productive — I never would have come up with all these great ideas by myself,” Siegel says. “To tell the truth, it really is a privilege serving as his translational collaborator.”

Welch’s C.V. details his astonishing productivity, listing more than 500 publications that he has authored or co-authored. His colleagues recognized his many accomplishments in 2004 by selecting him as only the sixth recipient of the Society of Nuclear Medicine’s Benedict Cassen Award .

At the special lecture he delivered as a Cassen Award winner, Welch emphasized the important contributions of researchers with whom he has collaborated over the decades.

“Awards are personal recognitions, but you don’t receive them without the people you work with,” Welch says. “There are 13 co-authors with whom I’ve published more than 20 papers. I made sure to put up a slide that listed all their names.”

Welch’s many collaborators include researchers in Japan and the Middle East. These international collaborations also allow him to satisfy his penchant for travel, a hobby he shares with his partner of five years, Mary “Mickey” Clarke, who works in the office of the University’s Vice Chancellor for Research. (Siegel notes with considerable pride that he catalyzed the relationship by separately inviting the two to dinner one New Year’s eve.)

The bronze nameplate on his desk, which reads “Michael J. Welch” in both English and Arabic, came from a trip to a bazaar in Cairo, Egypt. He has been to Japan, his favorite international destination, approximately 20 times.

|

Michael J. Welch Born: Stoke-on-Trent, England University positions: Professor of radiology, of chemistry and of molecular biology and pharmacology Interests: Elkhounds, four grandchildren and English soccer |

For a time, one of Welch’s other major personal interests was the competitive breeding and showing of Norwegian elkhounds. The hobby developed partially as a result of years of going to dog shows with his children, Lesley Tomlin, now a program coordinator in the Department of Biology in Arts & Sciences, and Colin Welch, a vice president for J.P. Morgan in New York City.

“The dog show trips were sort of for entertainment, although if you ask my kids now, they’ll say I forced them to go and they hated them,” Welch says, laughing. “I’m not quite certain that’s true.”

Tomlin groans and laughs when the topic of the dog shows is mentioned. It’s immediately clear that she’s accustomed to her dad doing his good-natured best to embarrass her.

“We all loved dogs, but there came a point when we were teenagers and still going to dog shows, and no teenager ever likes to do things with his or her parents,” she says.

As a dog breeder, Welch took his elkhounds to the Westminster Kennel Club in Madison Square Garden once, but more typically brought them to shows in a Midwestern circuit that ran from Wisconsin to Tennessee and Indiana to Kansas. He had a best in show dog once and at times had the number two overall elkhound nationally and a top elkhound in the obedience category.

Asked if elkhounds are particularly smart and trainable dogs, Welch chuckles and lets his dry, impish and very English sense of humor show again.

“Maybe one shouldn’t say this, but I think smart dogs don’t train particularly well,” he says, implying that a dog who’s intelligent enough will find ways to do whatever it wants to do.

Welch eventually found the elkhounds competing with travel, and now no longer keeps them. His four grandchildren now play a leading role in his personal life. Lesley has two daughters, Devin, 4, and Celia, 1, and Colin has two sons, C.J., 4, and Payton, 2.

“He loves to come over and play with his granddaughters, to go swimming or to go to the playground,” Tomlin says. “He tries to make it out to see the boys as often as he can, too.”

Welch’s other primary personal interest is watching English soccer with a group of friends at A.C. Grassi’s, a restaurant in St. Louis County.

“They’ve set up a room in back as their soccer-watching clubhouse,” Welch says.

“Interestingly enough, it’s not just a group of former English citizens. There are quite a few native St. Louisans in the group, and we all get together and root for Manchester United.”