What if all you had to do to receive a kidney transplant was ask someone to donate a kidney? It sounds easy, but for many people, it’s not.

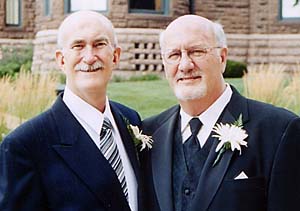

In 1996, Barry Hammond was aware that his kidney function was getting worse and the time frame for needing a transplant was getting closer. In 1957, Barry’s father had died from kidney disease at age 50, and Barry now was facing his 50th birthday. His only sibling was his brother, Brian.

Although Brian was aware of Barry’s health problems, it was hard for Barry to ask for one of his brother’s kidneys. He recalls standing on the front porch of Brian’s home one night after dinner when he finally posed the question. “It was a huge request — the biggest request I’ve ever made. It was easier asking my wife to marry me!” Hammond says.

Brian agreed and donated a kidney to Barry on Feb. 18, 1997.

More than 50,000 people in the United States are waiting for a kidney transplant. Every year, only 9,000 on the transplant waiting list get a kidney from someone who has died, while 16,500 on the list die. Transplants from living donors have the greatest chance of working for a long time and can happen quickly, often within a year.

A living kidney donor may be a family member or friend between the ages of 18 and 65. They must be healthy and have a blood type that is compatible with the recipient’s blood type.

But Amy Waterman, Ph.D., instructor in medicine at Washington University School of Medicine, has discovered something surprising. Many interested donors are not taken up on their offers to donate because the recipients are afraid the donors will be harmed. So many potential donor kidneys go unused.

Understandably, asking someone to donate a kidney is a daunting task. Living kidney donors have to undergo major surgery, stay in the hospital for three to five days and miss work for four to six weeks.

“But research shows that more than 92 percent of donors say they don’t have regrets and that they would make the same decision to donate again today,” Waterman says. “Some also say that donating a kidney is one of the most personally rewarding things they’ve ever done.”

For the past five years, Waterman has studied the barriers that recipients have to living donation, with the goal of increasing the number of kidney transplants from living donors. She has interviewed hundreds of donors and recipients and written brochures for both groups that are circulated at kidney transplant centers nationwide.

“There’s obviously miscommunication between these two groups,” Waterman says. “Donors see the short-term inconvenience of the surgery and recovery to be a small price to pay to improve the recipients’ health. But recipients don’t want the donors’ health to be harmed and feel like surgery would be an incredible burden for donors.”

Living kidney donation has been going on for 50 years, so there has been time to study the long-term effects on the donor’s health. Research suggests that living with one kidney does not affect how long a person lives, and kidney donation does not appear to increase the chance that the donor will develop kidney disease.

Also, a kidney from a living donor typically works better and lasts longer than a kidney from a donor who has died. Likely donors also can be tested ahead of time to find the donor whose kidney best matches the recipient, and a kidney from a living donor has a better chance of working normally as soon as the surgery takes place, making results better.

“Before they make a final transplant decision, kidney recipients need to understand how long the wait is for a kidney from a deceased donor and get their questions answered about living donation,” Waterman says. “It would be very sad if a recipient who had potential donors refused to consider living donation and died before a kidney from the waiting list became available.”

The full-time and volunteer faculty of Washington University School of Medicine are the physicians and surgeons of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.