(Republished with permission from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. This article originally ran in the Science & Technology section on Wednesday, August 6, 2008)

By Amanda Palleschi St. Louis Post-Dispatch

In the fall of 2005, Jacob Beckmann was hit by a roadside bomb in Iraq.

The blast left him with no feeling from his elbows down, and no feeling from his knees down through his feet.

After a brief stint at an Army hospital in Germany, Beckmann returned to his native Florissant. Two dozen surgeries and three years later, he has some function and strength in his hands. He had to learn how to tie his shoes again and shoot a gun with his left hand, but he said he knows he lucked out. Often, people with Beckmann’s type of injuries never regain feeling in their limbs.

“Jake can use his hands again,” his father said. “It was magic.”

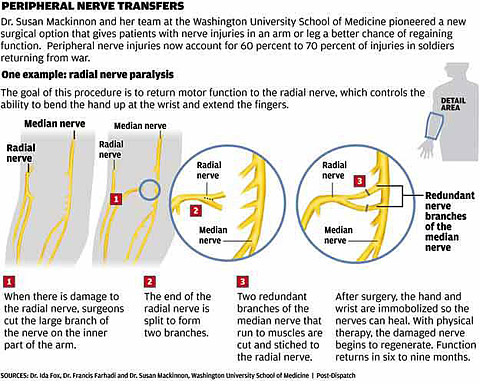

Numerous surgeons at hospitals around the city worked to make that magic for Beckmann. One of them, Dr. Susan Mackinnon, chief of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Washington University Medical Center, is a pioneer in a type of nerve reconstruction called peripheral nerve transfer. That surgery helped Beckmann regain use of his hands. The procedure requires a team of plastic surgeons, orthopedic surgeons and neurosurgeons. Only about a dozen doctors across the country perform the surgery.

Mackinnon has used the technique to repair nerves of victims of motorcycle accidents, gunshots and other violence. But peripheral nerve injuries make up 60 percent to 70 percent of all wounds in war, and this year Mackinnon plans to launch a website aimed at giving Veterans Affairs hospitals the surgical technique to save the limbs of more people like Beckmann.

‘A BRAND NEW MOTOR’

The difference between the more common nerve procedure and Mackinnon’s is “the difference between giving the nerve a new set of train tracks and giving the train a brand new motor,” said Dr. Justin Brown, a neurosurgeon with Barnes-Jewish Hospital’s Center for Advanced Medicine and a member of Mackinnon’s website development team.

The nerves reaching the arms and legs look much like tiny pieces of spaghetti. When struck by a bullet or injured during a car accident, they get so scarred that the nerve cannot regenerate, creating a loss of feeling from the point of impact down.

The most common procedure to fix peripheral nerve injuries is nerve grafting, a procedure that’s been practiced since World War II. A surgeon replaces the injured nerve with a piece of nerve taken from a place in the body where the nerve’s function is less vital, such as the inner part of a foot. The replaced nerve regenerates at a snail’s pace, the patient may never regain complete function, and could face amputation.

“It can be as slow as a millimeter a day for a nerve to regenerate after nerve grafting surgery,” Brown said.

Peripheral nerve transfer, Mackinnon’s specialty, involves taking a piece of a nerve from a part of the body closer to the injury. For example, with the arms, Mackinnon will borrow a tiny piece of the brachial plexus nerve, which begins in the neck. That piece of nerve is placed behind the scarred nerve, regenerating it. The injured nerve grows back at a much faster rate, and, depending on the timing of surgery and severity of the injury, the patient has a much better chance of regaining function. It’s a matter of regenerating at inches a day versus millimeters.

“This doesn’t leave you with the same numbness somewhere else in your body,” Brown said. “It can be way, way less dangerous.”

WORKING WITH THE VA

Jim Lorraine works from a military base in Tampa, Fla., to ensure that Special Operations soldiers get the best care they can get, whether inside the VA system or other places. He frequently refers patients to private caregivers like the ones at Washington University, often after they’ve been at a VA hospital. Private hospitals, he says, often serve as “finishing schools” in the treatment process.

He’s sent about five patients to Mackinnon, who has garnered something of a reputation as a rock star surgeon willing to go out of her way for those injured during tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, Lorraine says.

“The research I did showed that she is the leader in peripheral nerve transfer and peripheral nerve surgery, but more than that, she has a passion for helping casualties and for helping people. I talked to her about a number of casualties that immediately needed help. She made the time.”

Mackinnon’s idea has its critics, who say you can’t teach a surgical technique over the Internet. She points out that the website, which she hopes will be set up by the end of the year, is intended to give surgeons who are already experienced in treating nerve injuries on-site exposure to a new technique.

Today, Beckmann is back on his feet in Baghdad working for a private security company. When wounded, he also worked for a private firm as part of a security detail. His surgeries were covered by his firm. He knows those enlisted — like he was before the beginning of the war in 2003 — don’t always get so lucky.

“I got better medical care than some of the other people over here. At Walter Reed (Army Medical Center, in Washington), they don’t have as good of care as I probably received.”

apalleschi@post-dispatch.com | 314-340-8349

Copyright 2008 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Inc.