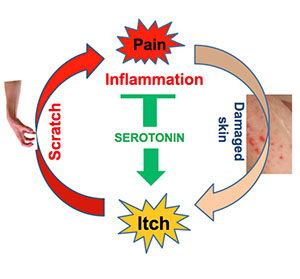

Turns out your mom was right: Scratching an itch only makes it worse. New research from scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that scratching causes the brain to release serotonin, which intensifies the itch sensation.

The findings, in mice, are reported online in the journal Neuron. The same vicious cycle of itching and scratching is thought to occur in humans, and the research provides new clues that may help break that cycle, particularly in people who experience chronic itching.

Scientists have known for decades that scratching creates a mild amount of pain in the skin, said senior investigator Zhou-Feng Chen, PhD, director of Washington University’s Center for the Study of Itch. That pain can interfere with itching — at least temporarily — by getting nerve cells in the spinal cord to carry pain signals to the brain instead of itch signals.

“The problem is that when the brain gets those pain signals, it responds by producing the neurotransmitter serotonin to help control that pain,” Chen explained. “But as serotonin spreads from the brain into the spinal cord, we found the chemical can ‘jump the tracks,’ moving from pain-sensing neurons to nerve cells that influence itch intensity.”

Scientists uncovered serotonin’s role in controlling pain decades ago, but this is the first time the release of the chemical messenger from the brain has been linked to itch, Chen said.

As part of the study, the researchers bred a strain of mice that lacked the genes to make serotonin. When those genetically engineered mice were injected with a substance that normally makes the skin itch, the mice didn’t scratch as much as their normal littermates. But when the genetically altered mice were injected with serotonin, they scratched as mice would be expected to in response to compounds designed to induce itching.

“So this fits very well with the idea that itch and pain signals are transmitted through different but related pathways,” said Chen, a professor of anesthesiology, of psychiatry and of developmental biology. “Scratching can relieve itch by creating minor pain. But when the body responds to pain signals, that response actually can make itching worse.”

Although interfering with serotonin made mice less sensitive to itch, Chen said it’s not practical to try to treat itching by trying to block the release of serotonin.

Serotonin is involved in growth, aging, bone metabolism and in regulating mood. Antidepressants like Prozac, Zoloft and Paxil increase serotonin levels to control depression. Blocking serotonin would have far-reaching consequences throughout the body, and people wouldn’t have a natural way to control pain.

Instead, Chen explained, it might be possible to interfere with the communication between serotonin and nerve cells in the spinal cord that specifically transmit itch. Those cells, known as GRPR neurons, relay itch signals from the skin to the brain. To work toward that goal, Chen’s team isolated the receptor used by serotonin to activate these neurons.

To do this, Chen’s team injected mice with a substance that causes itching. They also gave the mice compounds that activated various serotonin receptors on nerve cells. Ultimately, they learned that a receptor known as 5HT1A was the key to activating the itch-specific GRPR neurons in the spinal cord.

To prove they had the correct receptor, Chen’s team also treated mice with a compound that blocked that receptor, and those mice scratched much less.

“We always have wondered why this vicious itch-pain cycle occurs,” Chen said. “Our findings suggest that the events happen in this order. First, you scratch, and that causes a sensation of pain. Then you make more serotonin to control the pain. But serotonin does more than only inhibit pain. Our new finding shows that it also makes itch worse by activating GRPR neurons through 5HT1A receptors.”

As his team works to better understand the molecular and cellular mechanisms that control the cycle, Chen suggested that those who itch pay attention to mom’s advice and try not to scratch.

Funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Additional funding was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. NIH grant numbers: AR056318-01,

R01 DA019921, GM069027 and GM080558.

Zhao ZQ, Liu XY, Jeffry J, Karunarathne WKA, Li JL, Munanairi A, Zhou XY, Li H, Sun YG, Wan L, Wu ZY, Kim S, Huo FQ, Mo P, Barry DM, Zhang CK, Kim JY, Gautam N, Renner KJ, Li YQ, Chen ZF. Descending control of itch transmission by the serotonergic system via 5-HT1A-facilitated GRP-GRPR signaling. Neuron. vol. 84 (4), Nov. 19, 2014. Published online Oct. 30, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.003

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.