Beavers don’t brush their teeth, and they don’t drink fluoridated water, but a new study reports beavers do have protection against tooth decay built into the chemical structure of their teeth: iron.

The research team, which was led by scientists from Northwestern University, included Jill D. Pasteris, PhD, professor of earth and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

“This work is an excellent example of the structural-chemical novelty that we are still discovering in natural, biomineralized materials, such as tooth and bone,” Pasteris said.

This pigmented enamel, the researchers found, is both harder and more resistant to acid than regular enamel, including that treated with fluoride. This discovery is among others that could lead to a better understanding of human tooth decay, earlier detection of the disease and improving on current fluoride treatments.

Layers of well-ordered, carbonated hydroxylapatite “nanowires” are the core structure of enamel. The team led by Northwestern researcher Derk Joester, PhD, discovered in rodent teeth that it is the material surrounding the nanowires, where small amounts of an amorphous solid rich in iron and magnesium are located, that controls enamel’s acid resistance and mechanical properties.

Enamel is a very complex structure, making study of it challenging. Joester’s team is the first to show unambiguously that this “amorphous,” or unstructured, phase exists in enamel, and they are the first to show its exact composition and structure.

“We have made a really big step forward in understanding the composition and structure of enamel — the tooth’s protective outer layer — at the smallest length scales,” said Joester, lead author of the study and associate professor of materials science and engineering in Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science.

“The unstructured material, which makes up only a small fraction of enamel, likely plays a role in tooth decay,” Joester said. “We found it is the minority ions — the ones that provide diversity — that really make the difference in protection. In regular enamel, it’s magnesium, and in the pigmented enamel of beaver and other rodents, it’s iron.”

The unprecedented imaging study of tooth enamel at the nanoscale will be published Feb. 13 by the journal Science.

Dental caries — better known as tooth decay — is the breakdown of teeth due to bacteria. (“Caries” is Latin for “rottenness.”) It is one of the most common chronic diseases and a major public health problem, despite strides made with fluoride treatments.

According to the American Dental Association, $111 billion a year is spent on dental services in the U.S., a significant part of that on cavities and other tooth decay issues. A staggering 60 to 90 percent of children and nearly 100 percent of adults worldwide have or have had cavities, according to the World Health Organization.

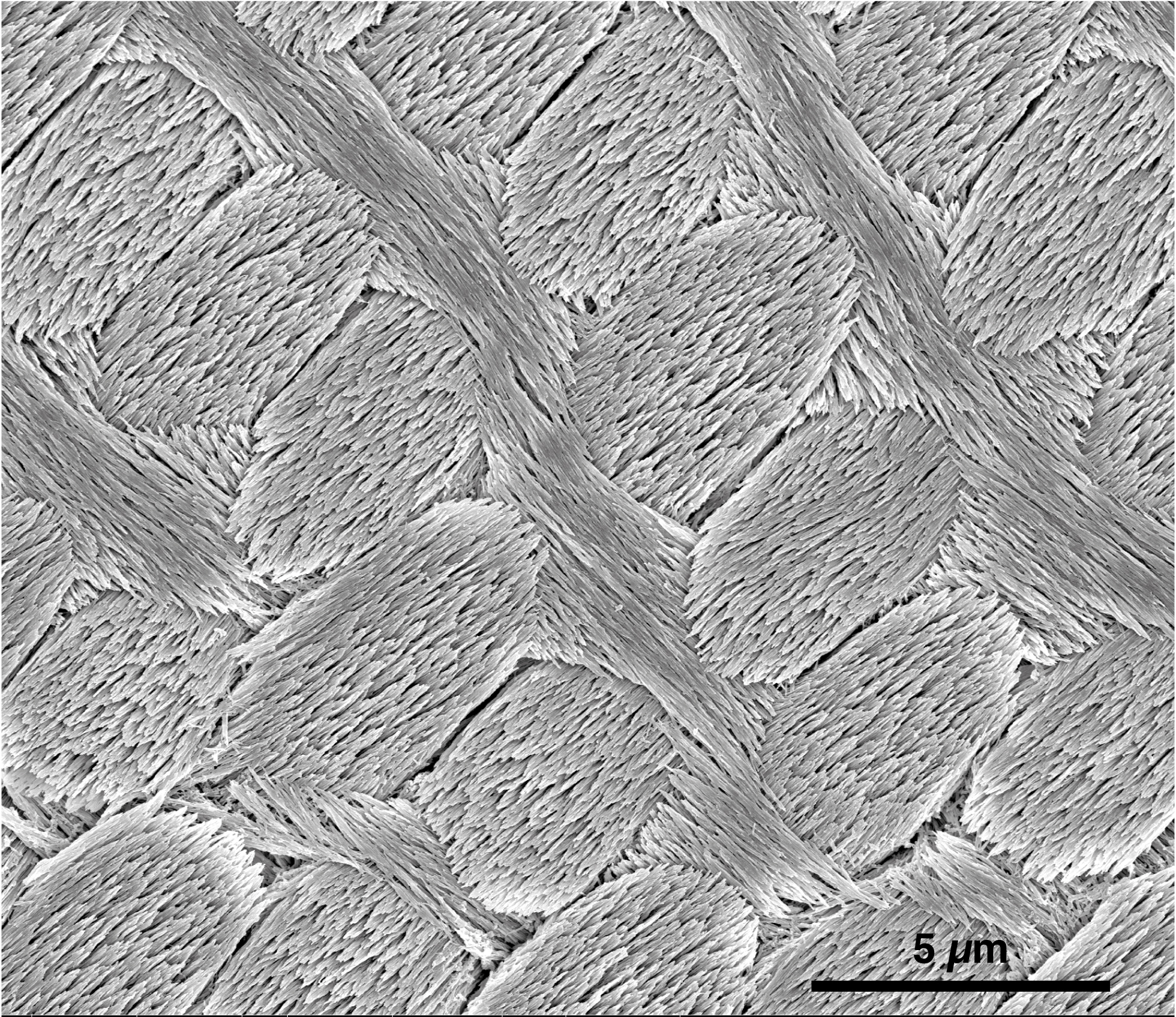

Scanning electron microscope image of inner enamel from the rat incisor. (Credit: Northwestern University) In a series of experiments on rabbit, mouse, rat and beaver enamel, Joester and his colleagues imaged the never-seen-before amorphous structure that surrounds the nanowires. They used powerful atom-probe tomography and other techniques to map enamel’s structure atom by atom. (Rodent enamel is similar to human enamel.)

Scanning electron microscope image of inner enamel from the rat incisor. (Credit: Northwestern University) In a series of experiments on rabbit, mouse, rat and beaver enamel, Joester and his colleagues imaged the never-seen-before amorphous structure that surrounds the nanowires. They used powerful atom-probe tomography and other techniques to map enamel’s structure atom by atom. (Rodent enamel is similar to human enamel.)

The researchers subjected the teeth to acid and took images before and after acid exposure. They found the periphery of the nanowires dissolved (the amorphous material), not the nanowires themselves.

The researchers next identified specific elements, such as iron and magnesium, in the amorphous material in the enamel and learned how they contribute to both the mechanical hardness and chemical resistance of enamel to acid dissolution.

Of particular interest to Joester and his colleagues was the pigmented enamel of the beaver’s incisors. Their studies showed it to be an improvement over fluoride-treated enamel in resisting acid. (The presence of iron gives the teeth a reddish-brown color.)

“A beaver’s teeth are chemically different from our teeth, not structurally different,” Joester said. “Biology has shown us a way to improve on our enamel. The strategy of what we call ‘grain boundary engineering’ — focusing on the area surrounding the nanowires — lights the way in which we could improve our current treatment with fluoride.”

The National Science Foundation (grants DMR-0805313, DMR-1106208 and DMR-1341391), the Northwestern University Materials Research Center (NSF – Materials Research and Engineering Center grant DMR-1121262), Northwestern’s International Institute for Nanotechnology and the Institute for Sustainability and Energy at Northwestern (ISEN) supported the research.

The title of the Science paper is “Amorphous Intergranular Phases Control the Properties of Rodent Tooth Enamel.”

A related paper will be published this week by the journal Frontiers in Physiology.

In addition to Joester and Pasteris, other authors of the paper are Lyle M. Gordon, PhD (first author), formerly with Northwestern, now with Pacific Northwest National Laboratory; Michael J. Cohen and Keith W. MacRenaris, PhD, of Northwestern; and Takele Seda, PhD, of Western Washington University.

This release is based on one written by Megan Fellman of Northwestern University.